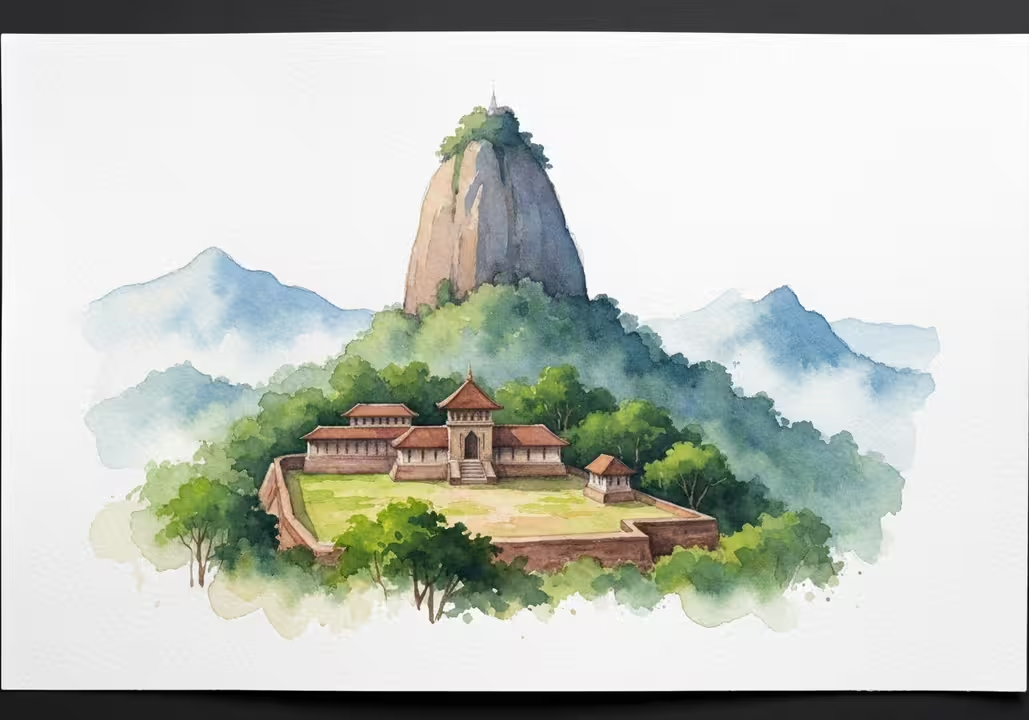

Rising 766 meters above the sun-scorched plains of north-central Sri Lanka, the mountain of Ritigala pierces the sky like a stone finger pointing toward enlightenment. Shrouded in perpetual mist and cloaked in dense forest, this isolated peak harbors one of the most enigmatic chapters in Sri Lankan Buddhist history—the story of the Pansukulika monks, an ascetic order who sought supreme enlightenment through extreme austerity, only to vanish mysteriously from historical records nearly a thousand years ago.

The Sacred Mountain

Long before the first stone was laid for any monastery, Ritigala held a sacred place in local legend. According to the epic Ramayana, when the monkey god Hanuman journeyed to the Himalayas to retrieve healing herbs for the wounded Lakshmana, he forgot their names and carried the entire mountain of Dronagiri back to Lanka. As he flew across the Palk Strait, five fragments slipped from his grasp and fell across the island. The largest of these, according to tradition, formed Ritigala—a mountain naturally blessed with medicinal plants of extraordinary potency.

Whether myth or metaphor, this legend reflects an enduring truth: Ritigala has always been recognized as a sanctuary of healing herbs. Modern botanical surveys have recorded a staggering 417 species of flora on the mountain, of which 96 are used in traditional Ayurvedic medicine. Three species—including Plectranthus elongatus, Madhuca clavata, and Thunbergia fragrans—are found nowhere else on Earth. The northern peaks are still known as “Aushada-kanda” and “Wannati-kanda”—Medicine Hill—testifying to centuries of herbal gathering by physicians and monks.

A Refuge for Ascetics

The first Buddhist presence at Ritigala dates to the 1st century BCE, when at least 70 caves were prepared for meditation by monks seeking solitude. Rock inscriptions from this period record donations by lay supporters, establishing a pattern of patronage that would continue for over a millennium. King Pandukabhaya, the legendary founder of Anuradhapura, is credited with constructing a reservoir at the mountain’s base around the 4th century BCE, providing water for the hermit monks who made their homes in the rocky caves.

For centuries, Ritigala remained a peripheral site—a retreat for monks who preferred the hardships of forest dwelling to the comfort of the great city monasteries. But in the 9th century CE, everything changed.

The Rise of the Pansukulikas

In 833 CE, King Sena I made a momentous decision. Troubled by what he saw as the growing wealth and laxity of the monastic establishment in Anuradhapura, he built an extensive monastery complex high on the slopes of Ritigala specifically for a reformist movement known as the Pansukulikas—literally, “the rag-robe wearers.”

The name reveals their philosophy. The Pansukulika monks vowed to wear only robes sewn from rags collected from garbage heaps or even shrouds taken from corpses—one of the thirteen austere practices (dhutanga) permitted by the Buddha himself. This was not mere poverty but deliberate renunciation, a protest against the comfortable, self-indulgent lifestyle they believed had corrupted the city monasteries. They sought to revive the radical simplicity of the Buddha’s original teaching, when enlightened monks wandered with nothing but a begging bowl and the rags on their backs.

Ritigala’s remote location, far from towns and trade routes, suited their austere vision perfectly. The monastery they built reflected their uncompromising philosophy in stone. Unlike every other Buddhist monastery in Sri Lanka, Ritigala has no stupas, no Buddha statues, no sacred Bodhi tree terraces—none of the usual objects of devotion and ritual. The architecture served only function: meditation, walking contemplation, and the most basic necessities of monastic life.

A Monastery Like No Other

The ruins of the Pansukulika monastery span approximately 120 acres of mountainside, connected by an intricate network of stone pathways. These walkways, constructed from precisely interlocking slabs of hewn stone, wind through the forest for kilometers, linking some 50 distinctive double-platform structures known as padhanaghara—meditation houses.

Each padhanaghara consists of two raised stone platforms aligned east to west, connected by a small stone “bridge” and surrounded by a miniature “moat.” The purpose of these unique structures continues to puzzle archaeologists. Were they meditation halls? Libraries? Ritual spaces? No definitive answer has emerged, adding to Ritigala’s air of mystery.

Equally enigmatic are the stone walkways themselves, which feature elaborate roundabouts—circular intersections where paths converge—a rare and unexplained feature in Sinhalese monastic architecture. The paths are engineered with remarkable precision, maintaining a consistent width of 1.5 meters and gently ascending the mountain slope.

Water management at Ritigala demonstrates sophisticated engineering knowledge. Twin ponds—the Kumbuk Wewa and Banda Pokuna—were carved from living rock with precision that still impresses modern engineers. A large rectangular refectory features a sunken stone courtyard with grinding stones and a massive stone trough, where monks prepared their single daily meal. Over a stone bridge lie the ruins of what appears to have been a monastery hospital, complete with stone mortars for grinding medicinal herbs and large stone basins that may have served as Ayurvedic oil baths.

Strikingly, the monastery complex contains no residential quarters. The monks themselves appear to have lived entirely in the natural caves scattered through the forest, embracing discomfort as the price of spiritual progress. The only decorative elements in the entire complex are elaborately carved urinal stones—one of the few concessions to dignity in an otherwise ruthlessly austere environment.

Wealth, Schism, and Decline

For nearly two centuries, the Pansukulikas enjoyed tremendous prestige. Royalty and common people alike revered these ascetic reformers as embodiments of the Buddha’s original teachings. But with prestige came donations, and with donations came the very wealth the Pansukulikas had originally rejected.

By the 11th century, the rag-robed monks had accumulated large estates and considerable political influence. The irony was not lost on critics: the movement that had begun as a protest against monastic wealth had itself succumbed to worldly success. Internal tensions led to a schism, and by the 12th century, the Pansukulikas had fractured into two rival factions.

The final blow came during the reign of King Vijayabahu I (1070-1110 CE), who undertook a comprehensive reform and reunification of the Buddhist monastic order. As part of these efforts, he confiscated the extensive holdings of the Pansukulikas. The monks withdrew from the capital at Polonnaruwa, retreating presumably to their forest strongholds. After this, they vanish entirely from historical records—their ideals, their practices, their ultimate fate lost to time.

The Forgotten Monastery

The abandonment of Ritigala was hastened by the catastrophic Chola invasions of the 10th and 11th centuries, which devastated much of northern Sri Lanka. With the collapse of centralized authority and the southward migration of the Sinhalese kingdoms, the northern dry zone fell into decline. Ritigala’s isolation, once its greatest asset, became a death sentence. Cut off from patronage and pilgrims, the monastery was swallowed by the encroaching jungle.

For nearly eight centuries, Ritigala lay forgotten, known only to local villagers as a haunted place where ancient spirits dwelled. The forest reclaimed what human hands had built. Massive trees pushed through carefully laid pavements. Vines strangled the stone platforms. The meditation halls of the rag-robed monks became the domain of leopards and wild boar.

Rediscovered

In 1872, colonial surveyor James Mantell, establishing triangulation points for the British survey of Ceylon, stumbled upon the ruins while ascending the mountain. His brief mention in an official report caught the attention of H.C.P. Bell, the first Archaeological Commissioner of Ceylon, who conducted an extensive exploration in 1893. Bell’s detailed report revealed the extraordinary scope and uniqueness of the site.

In 1941, recognizing its exceptional biodiversity, the British colonial government declared Ritigala a Strict Nature Reserve, protecting its 1,528 hectares of forest and medicinal plants. Modern conservation efforts have sought to balance archaeological preservation with environmental protection, a fitting tribute to monks who saw no separation between spiritual practice and the natural world.

Today, Ritigala stands as a testament to a remarkable but ultimately failed experiment in Buddhist reform. The stone pathways still wind through the forest, leading nowhere but deeper into green shadows. The meditation platforms remain, empty of the rag-robed monks who once sought enlightenment upon them. And on misty mornings, when clouds envelop the mountain peak, one can almost imagine ascetic figures moving silently along the ancient walkways, seeking the truth that always seems just beyond reach—a quest that ended mysteriously, leaving only stones and silence to mark their passage.

The Pansukulikas believed that by rejecting comfort, wealth, and worldly attachments, they could rediscover the pure dharma of the Buddha’s original enlightenment. Whether they succeeded remains one of Sri Lankan history’s enduring mysteries, hidden somewhere in the mist-shrouded forests of Ritigala, waiting perhaps for another seeker willing to tread the ancient stone paths toward truth.