The Horton Plains, a misty plateau in the central highlands of Sri Lanka, holds the secrets to one of the earliest agricultural experiments in South Asia. While the island is famous for its later hydraulic civilization, archaeological evidence from this region reveals a much older story of human interaction with the environment, dating back to the late Pleistocene epoch.

Prehistoric Farming

Radiocarbon dating and pollen analysis from peat deposits in Horton Plains have provided startling evidence of incipient plant management as early as 15,000 BC (17,000 years ago). This predates the Neolithic revolution in many other parts of the world.

The evidence suggests that prehistoric communities were not just passively gathering wild grains but actively managing them. They appear to have cultivated wild ancestors of:

- Oats (Avena sp.)

- Barley (Hordeum sp.)

- Rice (Oryza sp.) - appearing later, around 13,000 BC to 8,000 BC.

The Balangoda People

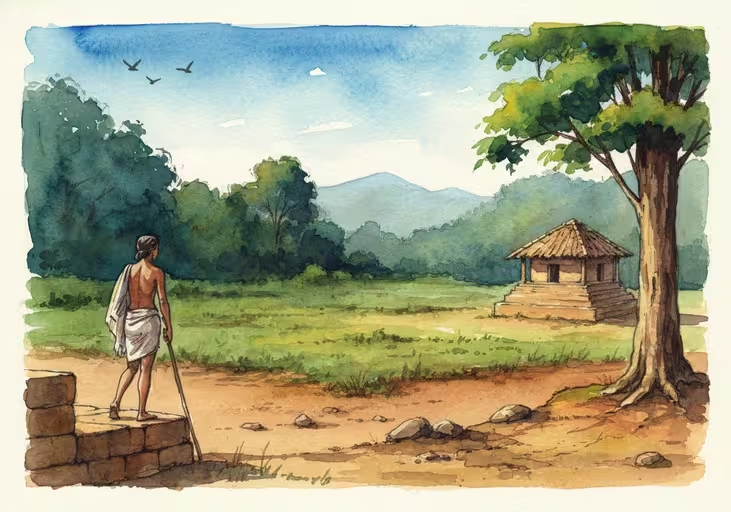

The architects of this early agriculture were likely the Balangoda Man (Homo sapiens balangodensis), the prehistoric inhabitants of Sri Lanka. These mesolithic hunter-gatherers were seasonal visitors to the Horton Plains. They likely moved up from the lowlands during the dry season to hunt and forage in the cool, wet highlands.

It appears they used fire as a tool to manage the landscape. By clearing forests through controlled burning, they created grasslands that attracted game animals and encouraged the growth of edible grains. This slash-and-burn technique (chena cultivation) is considered one of the earliest forms of landscape modification by humans in the region.

Environmental Impact

The transition from dense montane forest to the open grasslands we see today (patanas) was not entirely natural. It was, in part, an anthropogenic creation. The continuous management of these lands for thousands of years altered the ecosystem permanently.

This early experimentation with plant domestication laid the groundwork for the settled agricultural societies that would eventually emerge in the dry zone lowlands. It challenges the traditional view that agriculture was solely an imported technology, suggesting instead a long, indigenous process of adaptation and innovation.