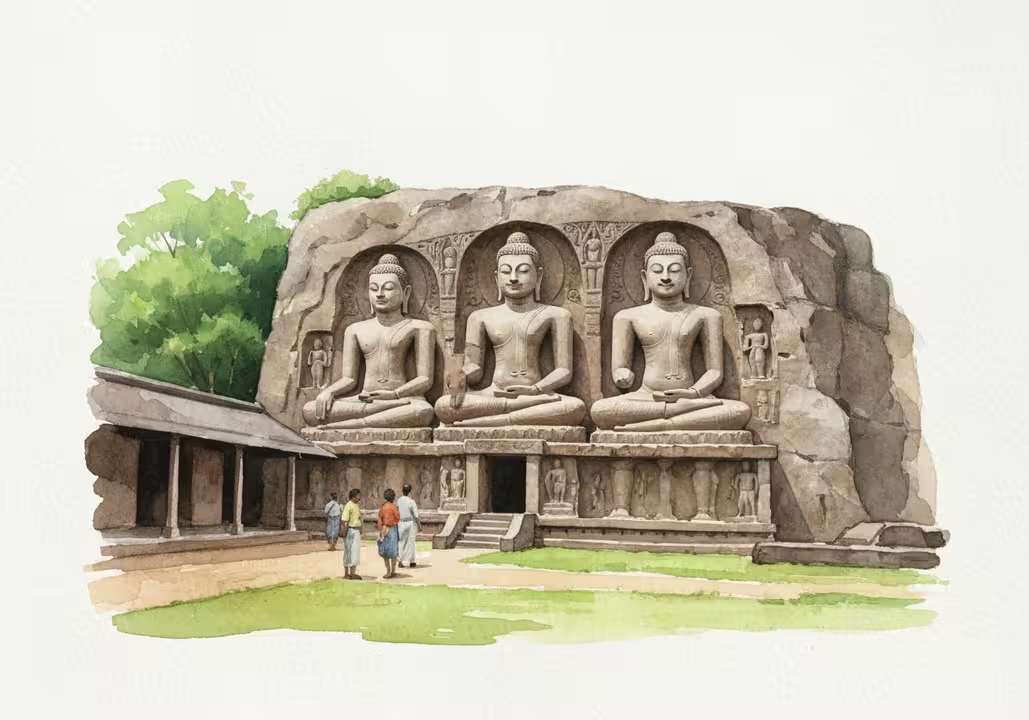

In the ancient city of Polonnaruwa, beneath the shade of protective canopies and surrounded by the whispers of pilgrims, four colossal Buddha statues emerge from a massive granite cliff face. These are the sacred images of Gal Vihara, originally known as Uttararama—the “northern monastery”—carved nearly nine centuries ago during one of Sri Lanka’s most illustrious periods of artistic and spiritual achievement.

A King’s Vision in Stone

The year was 1153 CE when King Parakramabahu I ascended to the throne of Polonnaruwa, inheriting a kingdom that had already established itself as the new political and religious center of Sri Lanka. But Parakramabahu was not content merely to rule; he envisioned a golden age of Buddhist revival and architectural magnificence that would echo through the centuries. Among his most ambitious projects was the transformation of a natural granite outcrop into a sacred temple complex that would become the crown jewel of Polonnaruwa’s religious monuments.

The king was a devout patron of Theravada Buddhism who sought to purify and unify the Buddhist sangha across the island. To this end, he convened a great council of monks at the Northern Monastery, where Gal Vihara was located. It was here, against the very rock face that would soon bear the Buddha’s image, that Parakramabahu drew up a code of conduct for the monastic community—a text inscribed in stone that still accompanies these magnificent sculptures.

The Art of Carving Mountains

The creation of Gal Vihara represents one of the most remarkable feats of medieval stoneworking anywhere in the world. Ancient artisans faced the formidable challenge of transforming a natural granite gneiss cliff into four distinct Buddhist images, each requiring extraordinary precision and artistic vision. To create the necessary canvas, workers carved nearly 15 feet deep into the living rock—the only example in Sri Lanka where natural stone was excavated to such an extent for sculptural purposes.

The tools were simple by modern standards: iron hammers and chisels, possibly supplemented by harder stones for the most delicate work. Yet what these artisans achieved with such implements defies easy explanation. The smooth, polished finish of the granite surfaces, the subtle modeling of facial features, and the flowing lines of robes and ornaments all speak to an advanced understanding of stoneworking that had been refined over centuries of Buddhist sculptural tradition.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the original appearance of these statues was even more spectacular than what visitors see today. According to renowned archaeologist Senarath Paranavithana, the images were originally coated in gold, their divine radiance amplified by the precious metal. Each large statue appears to have been enclosed within its own image house, as indicated by the remains of brick walls discovered at the site. These walls were likely covered with colorful frescoes, creating a total artistic environment that integrated architecture, sculpture, and painting into a unified spiritual experience.

Four Faces of the Awakened One

The Gal Vihara complex comprises four distinct sculptures, each carved to maximize the available rock surface and each representing different aspects of the Buddha’s life and teachings.

The largest of the seated figures towers 15 feet and 2.5 inches tall, depicting the Buddha in the dhyana mudra—the gesture of meditation. This magnificent image, considered by many to be the finest artistic sculpture in all of Sri Lanka, captures the essence of Buddhist contemplation. The Buddha sits in perfect composure, his hands resting in his lap in the timeless pose of one who has transcended the world’s illusions.

A smaller seated figure, measuring just 4 feet 7 inches in height, resides within an artificial cave called the Vidyadhara Guha. This intimate sanctuary was created by carving 4.5 feet into the solid rock, leaving four square pillars that frame the sacred space. Despite its smaller scale, this Buddha is no less magnificent in execution. The base of the lotus-shaped seat is carved with lions symbolizing fearlessness, while a delicate halo frames the Buddha’s head. Most remarkably, the statue is flanked by two four-armed deities—Brahma on the right and Vishnu on the left—representing the incorporation of Hindu divine protectors into the Buddhist cosmology, a characteristic feature of Sinhalese religious art.

The standing figure, rising to an impressive 23 feet, has been the subject of scholarly debate for over a century. The unusual crossed position of the arms and the contemplative, almost sorrowful expression led early interpreters to identify it as Ananda, the Buddha’s beloved disciple, mourning beside his master’s final resting place. However, subsequent detailed studies have established that this too is an image of the Buddha himself. Some scholars interpret the pose as representing the para dukkha dukkhitha mudra—“sorrow for the sorrow of others”—while others suggest it depicts the Buddha during his second week after enlightenment, when he stood gazing at the Bodhi Tree in gratitude for the shelter it had provided during his transformative meditation.

The reclining Buddha, at 46 feet and 4 inches in length, is not only the largest sculpture at Gal Vihara but also one of the largest stone carvings in all of Southeast Asia. This monumental work depicts the Buddha’s parinirvana—his final passing into the ultimate peace of nirvana. Every detail has been carefully considered: the feet are not entirely parallel as they would be for a sleeping Buddha, but rather the left foot is slightly drawn back, resting on the right—an iconographic feature specifically marking the moment of final liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

An Artistic Revolution

The sculptures of Gal Vihara represent a significant evolution in Sinhalese Buddhist art. When compared to earlier works from the Anuradhapura period, several distinctive features emerge. The Polonnaruwa artists rendered their Buddha images with broader foreheads, reflecting changing aesthetic ideals. The robes are carved with two parallel lines rather than the single line characteristic of earlier periods—a stylistic choice influenced by the Amaravati school of art from South India, demonstrating the vibrant exchange of artistic ideas across the Indian Ocean world during the medieval period.

Each image has been conceived to use the maximum possible area of the rock surface, with heights carefully calibrated to the natural dimensions of the stone itself. This marriage of artistic vision with geological reality speaks to a sophisticated understanding of both aesthetics and practical engineering that characterized the Polonnaruwa period at its zenith.

Preserving the Sacred

For nearly nine centuries, the Gal Vihara statues have withstood the relentless forces of nature and time. Environmental factors—weathering, erosion, and the persistent growth of moss and lichen—pose ongoing challenges to these granite masterpieces. Human activity, too, has taken its toll, as generations of pilgrims and tourists have touched and climbed upon the sacred images.

Recognition of Gal Vihara’s universal significance came with its designation as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site “Sacred City of Polonnaruwa.” Today, the Sri Lanka Department of Archaeology oversees the site’s protection, implementing comprehensive conservation measures. In the 1960s, a large sheltering roof was constructed over the statues to protect them from the elements, though this practical addition has been a source of aesthetic debate among visitors who lament the loss of the sculptures’ original open-air setting.

More recently, conservation has entered the digital age. The Department of Archaeology has partnered with international organizations including UNESCO and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation to employ cutting-edge 3D scanning technology. These detailed digital records document the current condition of each statue with unprecedented precision, providing both a baseline for monitoring future deterioration and a permanent record should restoration become necessary. Balancing accessibility with preservation remains an ongoing concern, as site managers work to ensure that future generations can experience these masterpieces while protecting them from the inevitable wear of countless footsteps and admiring hands.

A Living Legacy

Today, Gal Vihara stands as the most visited monument in Polonnaruwa, drawing pilgrims, scholars, and travelers from around the world. For Buddhist devotees, these are not merely works of art but living presences of the Enlightened One, worthy of offerings and veneration. For art historians, they represent the pinnacle of medieval Sinhalese sculptural achievement. For all who stand before them, they offer a profound encounter with human creativity and spiritual aspiration.

In the interplay of light and shadow across polished granite, in the serene faces that have gazed outward for centuries, and in the massive forms that seem both monumentally solid and weightlessly transcendent, the artisans of King Parakramabahu’s court achieved something truly timeless. They carved not just stone, but a vision of enlightenment itself—one that continues to inspire awe and devotion nearly a millennium after the last chisel stroke was made.